The tagline of this blog for the past few months has been ἀνέχου καί ἀπέχου. This can be translated (more poetically to my mind, and carrying some of the symmetry present in the Greek) as “bear and forebear,” or in a more approachable fashion as “endure and renounce.”

A pretty stern admonition it seems. This is often reported as the slogan of Epictetus (seen on the book on which he’s lounging), and its Latin counterpart (sustine et abstine) can be seen often in other venues as well. So the assumption that Stoicism is about quashing all desire seems just a quick step away. But, we’d be missing an important issue. Epictetus does tell us to abandon somethings, and postpone others for the present, but the issue is more complex.

A pretty stern admonition it seems. This is often reported as the slogan of Epictetus (seen on the book on which he’s lounging), and its Latin counterpart (sustine et abstine) can be seen often in other venues as well. So the assumption that Stoicism is about quashing all desire seems just a quick step away. But, we’d be missing an important issue. Epictetus does tell us to abandon somethings, and postpone others for the present, but the issue is more complex.

There’s an interesting issue here which gets lost in the English translation.

There’s more than one word for desire used in the Stoic sources. One (ὄρεξις) which is used in the context of desire for virtue, or good things. And a second word for desire (ἐπιθυμία) which is inordinate desire for vicious things or pleasures, lust.

ὄρεξις is one of the things listed as “up to us” in the Enchiridion 1, by the way. So it clearly can’t be one of those things we’re supposed to abandon or postpone, right? It’s what we’re training with and for. Here is why the English “desire” as a catch-all for both Greek terms is a problem for we English speakers. We might end up making a (reasonable mistake in this case) misapprehension because we’re using the same word for two different lexemes in the Greek. We may not even know this is occurring, if we don’t read Greek or have it pointed out to us.

So, when we are trying to switch our focus from lusting-desire (for pleasures) to grasping-desire (for virtue), we’re not trying to quash “desire” per se, but we’re trying to quash this yearning or hankering for vicious things.

We should have a grasping-desire for progress, for virtue, for wisdom. We should grasp for courage, justice, wisdom, and self-control.

We should avoid lusting after body-pleasure, social-rank, intellectual-pride, etc.

Using our ὄρεξις is an entirely acceptable place to be, while we avoid the dangers of ἐπιθυμία.

**cue shooting start**

Links:

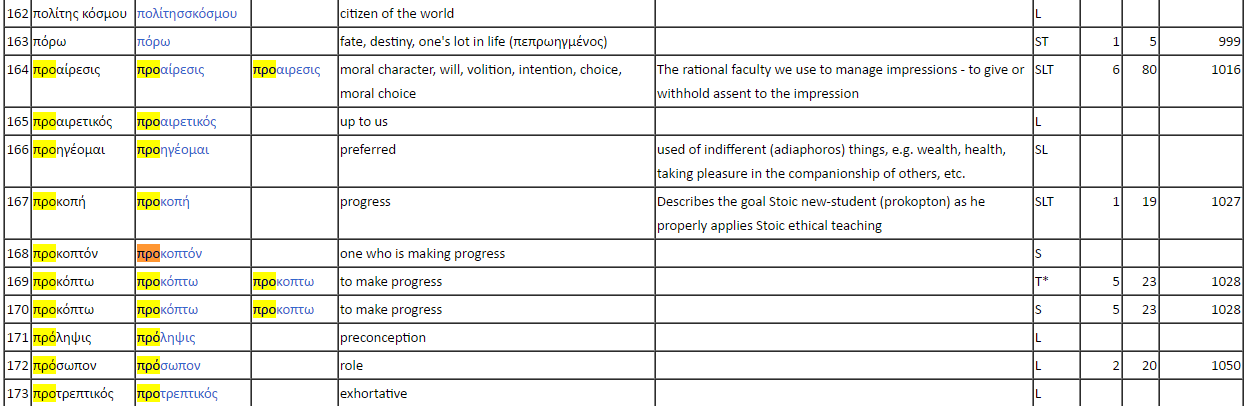

Vocabulary:

– Perseus, ὄρεξις

– Perseus, ἐπιθυμία

– Strong’s, ὄρεξις

– Strong’s, ἐπιθυμία

You must be logged in to post a comment.