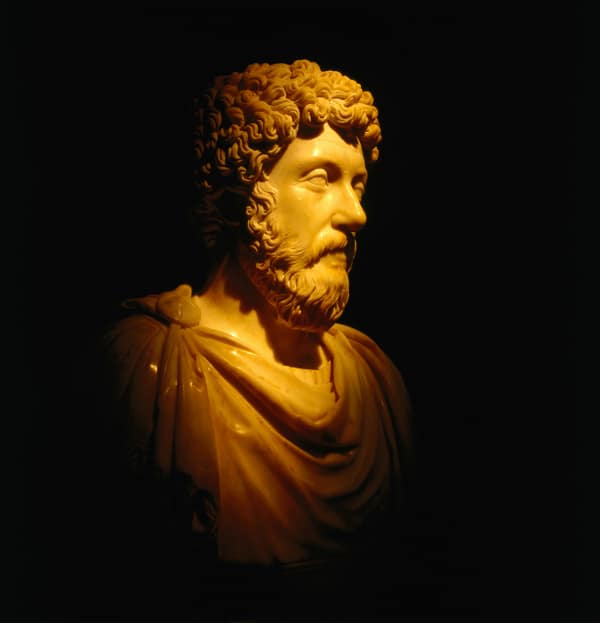

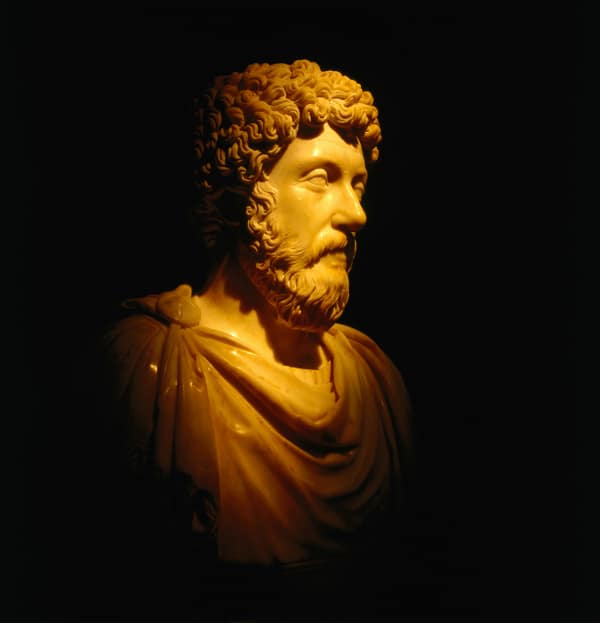

“Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Be one.”

— Meditations X.16

One of the things which often seems to be forgotten, is that the title which is traditionally given to what we call “Meditations” in English is Τὰ εἰς ἑαυτόν or “Things to one’s self” and sometimes just “To himself.” Marcus never intends his notes to be read by another, and certainly that matters when we’re interpreting his writings.

Below are a few reasons why the above passage (and others like it) likely don’t apply to the modern Stoic student.

1. Marcus was already firmly studied in Stoicism.

Marcus had several private tutors in philosophy from a young age. Whether it be Fronto or Rusticus, during the formative years of his life he had a solid philosophical influence. Most of us come to philosophy in adulthood, and we lack the decades of grounding that Marcus had. When he admonishes himself from study to action, he knows this. It simply doesn’t apply to the nascent προκόπτων in the same way. We ought to prefer practice to theory alone, but we do need the theory.

2. Marcus had training in Stoic moderation (ἄσκησις )

From an early age, Marcus was used to the Greek regimen of moderation and simplicity. Early on in the Meditations, he recounts how his mother and others would try and dissuade him from these practices. Most of the 21st century Stoic practitioners are not preforming the physical training that we see over and over in Musonius, Epictetus, and Marcus. True Stoic moderation appears extreme to those of us steeped in a level of indulgence that would be staggering to the ancients. For this reason, Marcus was already practiced in the things which for most of us are mere theory, cold showers aside.

3. Marcus was in a particular and rare circumstance.

As the Emperor of a large empire, Marcus had external demands and duties which are radically different from ours. This is not to enter a value judgment about which are better, easier, or preferable, it’s a mere fact that they are different. The Roman Stoics had more of a focus on roles and duties than their predecessors; and Marcus would have felt this strongly. For him, his time is better spent in embodying the virtues he has already come to know than it would be in further study. We, however, have need to inculcate these points in our daily lives, and this requires study and learning.

4. Marcus had access to resources we do not (probably).

It is generally accepted that the works of Epictetus to which Marcus had been introduced was probably some version of Arrian’s notes: The Discourses. We also know that there were four additional Books which have been lost to time. It seems likely to me that Marcus had access to those lost books. Since we are working with only a fraction of the Stoic record, we have to work more intensely and diligently on them than those who had access to more. Marcus may admonish himself to have fewer books, but he had access to ones we do not.

5. Marcus was living and operating in a world where Stoicism was a major social influence.

Any educated Roman of Marcus’ time would have been familiar with Stoic philosophy, at least the broad strokes. Greek philosophy helped shape Rome in profound and serious ways. In may ways, Marcus practice while extraordinary for an Emperor, was relatively common in and of itself. We students of ancient philosophy, especially those of us seeking to make philosophy a way of life, are outliers. Rather than stepping into the well worn ruts of those who have gone before, we find ourselves forging new paths, and carving roads into a wilderness 2,000 years deep. This distance of time requires different strategies, tools, and work than Marcus himself needed.

It seems to me that there is much to gain from Marcus’ writings, but it is also important to take from them judiciously. I cannot help but see parallel struggles (and sometimes the exact same ones) in Marcus’ writings as I have in my own life. Yet some are unique to his time, others unique to his person. So when Marcus tells himself to pair down his bookshelf, waste no more time in contemplation, etc., these might not be true for us.

I certainly encourage frequent reading of the work, and a careful application of a critical rule which shifts what’s applicable to us and what is not. So before you set aside something which might seriously affect your training, consider whether that in fact applies to you.

Thanks to the readers of this blog, since it is very likely without you I would not have been able to reach the point where I was included in Stoicism Today’s compendia, and from there to Wikipedia!

Thanks to the readers of this blog, since it is very likely without you I would not have been able to reach the point where I was included in Stoicism Today’s compendia, and from there to Wikipedia!

You must be logged in to post a comment.