Today I find that my prohairesis is presented with impressions of the physical and mental manifestations of anxiety. Two questions then must follow.

The first: is this impression actually what it reports to be? So I must know what the impression tells me it is. An impression which carries with it the symptoms of anxiety, recommends that some current or future apparent evil exists. In a less technical vocabulary, it presents as if there is or will be some serious threat. So I look at the situation and I asked myself, does there appear to be such a threat? Is the apparent evil a real evil? I’m forced to admit that the answer is no to both of these questions. So the impression is not in fact what it reports to be, it is not the thing itself merely an impression of it.

The second question is the following: is this a situation which is in my exclusive jurisdiction? I also find that answer to be no. And looking at the training of the stoics I understand that proto-passions exist, impressions are presented to the ruling faculty, and many of them occur before we have a chance to attach a judgment to them and assent. However, these could be proto-passions, or they could be impressions incorrectly assented to. So either way I’m dealing with something that is not as it appears to be.

The judgment is up to me, and the proto-passion is not.

Let us assume then for the sake of argument, that I am experiencing an internal impression which is presented to me without my assent. In this case my internal state is experiencing something which is more like that of the body as it experiences weather, rather than as the moral will experiences the results of a judgment. Some days, the weather is sunny and pleasant. Some days it is wet and dreary. And yet other days, the weather presents itself as frightful, terrible terrible; and even a threat to living beings. Today my internal weather feels somewhat like this latter one.

But it is the case that this is not fully up to me, it is an aprohairetic thing, and therefore I must determine that it is nothing to me. When the weather is bad, that doesn’t imply that we’ve done something wrong, it doesn’t indicate that we are bad, or in some way responsible or guilty. Today these anxious feelings are similar. I’m experiencing some bad weather, and it is not indicate a fault on my part. Yet, I must take care not to fall into a fault merely because of this context.

So what is my role here? It is to handle these impressions rightly, it is to respond to the situation as presented to me in the best way possible. If we’re playing cards, and we are dealt a bad hand, it does not mean that we are a bad player. Even the very best of players sometimes draw bad hands. How we use that bad hand indicates whether we are a good or bad player, or rather how we play despite it. So today I would like to be a good player, to handle the situation as it is presented to me in accordance with the nature of things. That is my goal, and my recommendation. It is not always pleasant to be dealt the bad hand but it is my game to play, and play well. Sometimes, however, we play from a position of disadvantage.

Additional resources on technical points:

- Prohairesis: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prohairesis

- Impressions: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phantasiai

- Proto-Passions: https://donaldrobertson.name/tag/proto-passions/

I’ve had experience using several prayer/meditation aids in the past from several traditions, some I’ve studied as an adult and one was a core practice of my religious upbringing. It is interesting how it seems we often circle back to core parts of our early indoctrination, even if other core parts are set aside. I’ve had the opportunity to sit as a neutral observer in related services and religious functions, and I’m always struck by how far away my path has taken me from some of those concepts and beliefs, and how close others still are.

I’ve had experience using several prayer/meditation aids in the past from several traditions, some I’ve studied as an adult and one was a core practice of my religious upbringing. It is interesting how it seems we often circle back to core parts of our early indoctrination, even if other core parts are set aside. I’ve had the opportunity to sit as a neutral observer in related services and religious functions, and I’m always struck by how far away my path has taken me from some of those concepts and beliefs, and how close others still are. Recently, I discovered a tool used to pass the time in Greece and Cyprus called κομπολόι (kompoloi). These are used in a “quiet” and “loud” fashion as a sort of “fidget-device” and are really devoid of any current meditative or religious practice.

Recently, I discovered a tool used to pass the time in Greece and Cyprus called κομπολόι (kompoloi). These are used in a “quiet” and “loud” fashion as a sort of “fidget-device” and are really devoid of any current meditative or religious practice. Longtime readers will remember that

Longtime readers will remember that

Time marches on, the sands of the hourglass continue to fall. We’ve made yet another trip, as a planet, around our sun. As a small aside, it’s interesting to me how many religious and cultural traditions mimic this act with circumabulation about central objects of importance, a microcosmic reflection of the order of the cosmos.

Time marches on, the sands of the hourglass continue to fall. We’ve made yet another trip, as a planet, around our sun. As a small aside, it’s interesting to me how many religious and cultural traditions mimic this act with circumabulation about central objects of importance, a microcosmic reflection of the order of the cosmos. We have two topics today, both dealing with speculation and the color of our thoughts. In the first, Marcus lists some of the paragons of the mind on classical antiquity: Hippocrates, Heraclitus, et al. Despite how these contributed to the social weal, they passed away. There’s a tinge of irony here, in some of these deaths as well: the manner or context of their dying contrasted with the focus of their study, or speculation. Marcus is using this a meditation on death and on meaning. We might spend a significant portion of our time speculating on (for his concern and ours) virtue, yet the sand continues to trickle through the hour glass, and we have no idea how much is left.

We have two topics today, both dealing with speculation and the color of our thoughts. In the first, Marcus lists some of the paragons of the mind on classical antiquity: Hippocrates, Heraclitus, et al. Despite how these contributed to the social weal, they passed away. There’s a tinge of irony here, in some of these deaths as well: the manner or context of their dying contrasted with the focus of their study, or speculation. Marcus is using this a meditation on death and on meaning. We might spend a significant portion of our time speculating on (for his concern and ours) virtue, yet the sand continues to trickle through the hour glass, and we have no idea how much is left. One of the traits (we may go even so far as to say virtues) of the Cynic is shamelessness or ἀναίδεια in the Greek. Although Diogenes was held in relatively high esteem by the early Christian church, they drew a line here, generally, and didn’t think overly well of the practice. Diogenes’ line of reasoning is, that anything which is in accordance with nature cannot be evil (the Stoics would agree), and anything which isn’t evil has no need to be hidden. Ah, we see here the seeds of Marcus’ reasoning then, too!

One of the traits (we may go even so far as to say virtues) of the Cynic is shamelessness or ἀναίδεια in the Greek. Although Diogenes was held in relatively high esteem by the early Christian church, they drew a line here, generally, and didn’t think overly well of the practice. Diogenes’ line of reasoning is, that anything which is in accordance with nature cannot be evil (the Stoics would agree), and anything which isn’t evil has no need to be hidden. Ah, we see here the seeds of Marcus’ reasoning then, too! We can take the Cynic ἀναίδεια in a Stoic fashion. We can change or remove those behaviors and thoughts that would lead to a rightful feeling of shame, correct them before they work their way out into speech and deed. Which of our thoughts would rightfully feel shameful about? These are the things to work on.

We can take the Cynic ἀναίδεια in a Stoic fashion. We can change or remove those behaviors and thoughts that would lead to a rightful feeling of shame, correct them before they work their way out into speech and deed. Which of our thoughts would rightfully feel shameful about? These are the things to work on. After a post in

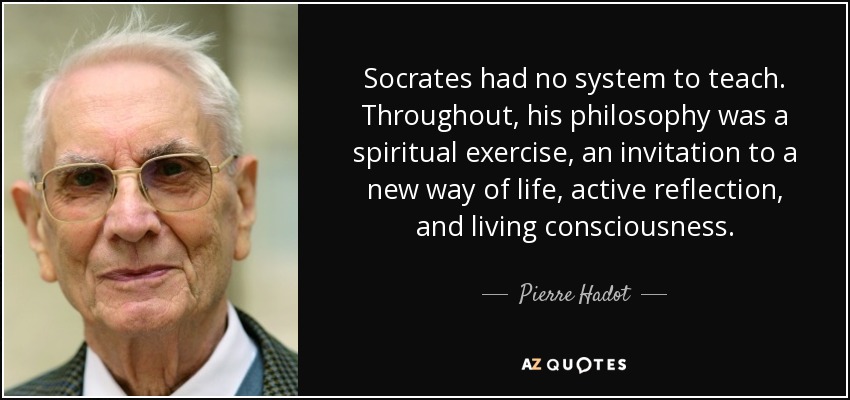

After a post in  From the words above, we can look at some English words which help us see what Socrates is doing inside, he’s turning his thoughts inward, examining himself, contemplating, inspecting, looking out for something, etc. His practice involves him standing, sometime shortly, other times for a very long time, and engaging in this work. He stands away, so it’s personal, but he does it wherever he happens to be, so it’s not private, and it is without concern for time or the events of others, so it is not a public display. I hope this delimits the practice somewhat. Additional, this

From the words above, we can look at some English words which help us see what Socrates is doing inside, he’s turning his thoughts inward, examining himself, contemplating, inspecting, looking out for something, etc. His practice involves him standing, sometime shortly, other times for a very long time, and engaging in this work. He stands away, so it’s personal, but he does it wherever he happens to be, so it’s not private, and it is without concern for time or the events of others, so it is not a public display. I hope this delimits the practice somewhat. Additional, this

I have just finished reading the section of Plutarch’s De Moralia “On Curiosity.” The Greek word in question is a bit difficult to translate, so you also see “On Being a Busybody” used.

I have just finished reading the section of Plutarch’s De Moralia “On Curiosity.” The Greek word in question is a bit difficult to translate, so you also see “On Being a Busybody” used.

You must be logged in to post a comment.