Seneca,

I would have my mind of such a quality as this; it should be equipped with many arts, many precepts, and patterns of conduct taken from many epochs of history; but all should blend harmoniously into one. “How,” you ask, “can this be accomplished?” By constant effort, and by doing nothing without the approval of reason.

This presents an image of a sort of eclecticism, picking up bits from here and there, assembling them into one synthetic whole. I’m not sure that I can agree, on the face. However, with the qualifier of reason as the test, it may very well end up less scattered than it might first appear.

And if you are willing to hear her voice, she will say to you: “Abandon those pursuits which heretofore have caused you to run hither and thither. Abandon riches, which are either a danger or a burden to the possessor. Abandon the pleasures of the body and of the mind; they only soften and weaken you. Abandon your quest for office; it is a swollen, idle, and empty thing, a thing that has no goal, as anxious to see no one outstrip it as to see no one at its heels. It is afflicted with envy, and in truth with a twofold envy; and you see how wretched a man’s plight is if he who is the object of envy feels envy also.”

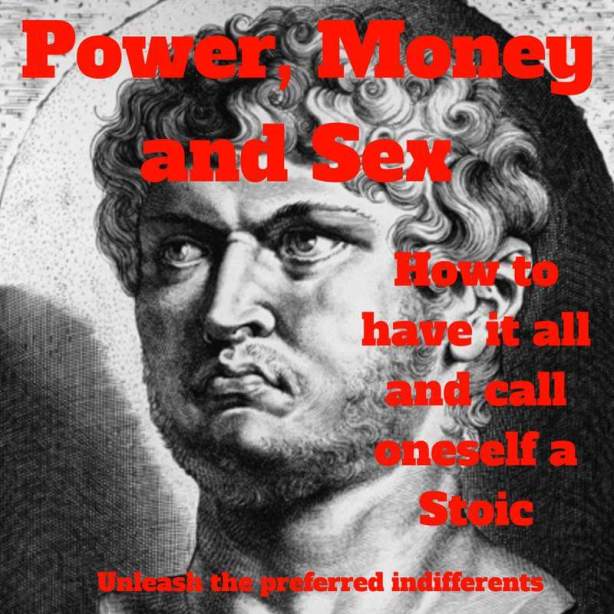

A clear call to renounce the indifferent things. It’s a hard line to take, and there are many voices in our time, as there were in yours, that such a thing is one of the greatest follies.

But this perennial challenge seems to echo across time, cultures, peoples, and every aspect of human life. There must be something there for those that answer this call.

We often wonder what the cost of truth is. Philosophy is not a “come as you are” club, it demands you change. It demands that you make yourself worth of Truth. Here, the cost is clearly laid out.

How many will pay it?

Farewell.

For those of you who have been following the blog for the past two and a half years, thank you. If you wouldn’t mind also

For those of you who have been following the blog for the past two and a half years, thank you. If you wouldn’t mind also

I have just finished reading the section of Plutarch’s De Moralia “On Curiosity.” The Greek word in question is a bit difficult to translate, so you also see “On Being a Busybody” used.

I have just finished reading the section of Plutarch’s De Moralia “On Curiosity.” The Greek word in question is a bit difficult to translate, so you also see “On Being a Busybody” used.

You must be logged in to post a comment.