Epictetus mentions exile quite a bit in the Discourses and also in the Enchiridion. Considering that he was himself exiled, and exile was a fairly common occurrence during his time, this is not surprising. We don’t have exile in the traditional sort so much these days in the west. We have imprisonment, death, sickness, and many of the other plights of men.

But exile, not so much.

Or is that true? Maybe we still have exile, but of a different sort. Surely, very rarely are we banished from our country, stripped of the rights of citizenship and sent away as a foreigner to a foreign land… right? If one travels from Maine to California, every place you stop will have McDonald’s and the dollar. They share governmental structures, taxes, and the like. The language is passingly similar. But the countries and the people are not non-different.

We might find ourselves living far from our birth places, far from our people, and in countries strange to us. So, maybe it is a good thing that Epictetus harps on exile as he does. I know it’s currently relevant for me.

“I must be put in chains. Must I then also lament? I must go into exile. Does any man then hinder me from going with smiles and cheerfulness and contentment?”

— Epictetus, Discourses I.1

Suffering and distress are internal affairs. While the outside actions and contexts of our lives may not be entirely up to us, the attitudes and the judgement we make about them are. The layman is sent away from home for work or for some other purpose, separated from the people and land he loves. He views himself injured, and he is distressed.

But it is up to us to determine if we are injured, diminished, or distressed. So we must go, must we also go unhappy? No.

“[T]o study how a man can rid his life of lamentation and groaning, and saying, “Woe to me,” and “wretched that I am,” and to rid it also of misfortune and disappointment and to learn what death is, and exile, and prison, and poison, that he may be able to say when he is in fetters, “Dear Crito, if it is the will of the gods that it be so, let it be so”. “

— Epictetus, Discourses I.4

Here is the crux. We must study. We have spent years and decades inculcating judgments about the world. We’ve been training for our whole lives to make the wrong decision. So we must train now, with the diligence of the truly dedicated to overturn these unnatural and learned defaults.

Epictetus’s teachings have a deeply religious character, for him, turning to philosophy is piety. Religion is a comfort for many, and some a nigh-insurmountable obsticle. Regardless, this “giving over” of things external has a lesson for the Stoic philosopher. Let us leave those things which are not ‘up to us’ to others.

“[I]n a word, neither death nor exile nor pain nor anything of the kind is the cause of our doing anything or not doing; but our own opinions and our wills. “

— Epictetus I.11

How can we truly train for equanimity and wisdom in the face of death when something such as sickness or exile torments out souls? How can we progress at the biggest thing, when the little things tear us down? Exile does not make us unhappy, or opinions and our will do. Stilbo, Epictetus, and all the others would have treated it an evil were it so.

“[N]o man sends a cowardly scout, who, if he only hears a noise and sees a shadow anywhere, comes running back in terror and reports that the enemy is close at hand. So now if you should come and tell us, “Fearful is the state of affairs at Rome, terrible is death, terrible is exile; terrible is calumny; terrible is poverty; fly, my friends; the enemy is near”; we shall answer, “Begone, prophesy for yourself; we have committed only one fault, that we sent such a scout.” “

— Epictetus, Discourses I.24

We look to our judgments of the world to help us navigate it. Yet, we’ve trained our ruling faculty to react to every little thing. This is not helpful for us. Instead, we must teach ourselves to judge things aright, that we see clearly, and thereby choose projects and actions, or inactions, conducive to our own virtue.

“In the schools what used you to say about exile and bonds and death and disgrace?”

I used to say that they are things indifferent.

“What then do you say of them now? Are they changed at all?”

No.

“Are you changed then?”

No.

— Epictetus, Discourses I.30

It’s very easy to learn the theory. It is much harder to practice it, and harder still to hold to it in the crisis. But life happens in extremis. It’s only at the edge of the envelope that we see what we’ve learned. So have we changed? Have we left the field over which philosophy can assist? No, we have not.

“In what cases, on the contrary, do we behave with confidence, as if there were no danger? In things dependent on the will. To be deceived then, or to act rashly, or shamelessly or with base desire to seek something, does not concern us at all, if we only hit the mark in things which are independent of our will. But where there is death, or exile or pain or infamy, there we attempt or examine to run away, there we are struck with terror.”

— Epictetus, Discourses II.1

Despite our trainings, we still fall short. When the precepts and values which we have learned have not yet been internalized, we are deceived.

“Let others labour at forensic causes, problems and syllogisms: do you labour at thinking about death, chains, the rack, exile; and do all this with confidence and reliance on him who has called you to these sufferings, who has judged you worthy of the place in which, being stationed, you will show what things the rational governing power can do when it takes its stand against the forces which are not within the power of our will.”

— Epictetus, Discourses II.1

One of the key features of Epictetus’s thought-model of the cosmos, is that the philosopher is appointed by the divine to his station. He is a like a soldier on the wall, with clear duties and obligations. He has a mission, and it is clear and explicit: but not easy. He has to rectify his soul. He must correct his prohairesis (προαίρεσις) and hêgemonikon (ἡγεμονικόν), his moral will and ruling faculty.

“For if a man can quit the banquet when he chooses, and no longer amuse himself, does he still stay and complain, and does he not stay, as at any amusement, only so long as he is pleased? Such a man, I suppose, would endure perpetual exile or to be condemned to death.”

— Epictetus, Discourses II.16

The Great Banquet of Life is one of my favorite Stoic allegories. Maybe because my family took table manners to be particularly important, I feel predisposed to understand how that microcosm can be representative of the cosmos-per-se.

A good dinner guest takes what he is served with gratitude and humbleness. He does not stretch for his hand and take what is not presented to him. He does not say that it is of poor quality or not to his liking. He takes what he needs, and passes the rest on.

“Dare to look up to God and say, “Deal with me for the future as thou wilt; I am of the same mind as thou art; I am thine: I refuse nothing that pleases thee: lead me where thou wilt: clothe me in any dress thou choosest: is it thy will that I should hold the office of a magistrate, that I should be in the condition of a private man, stay there or be an exile, be poor, be rich? I will make thy defense to men in behalf of all these conditions. I will show the nature of each thing what it is.” “

— Epictetus, Discourses II.16

Epictetus is empowered by his piety, something which I can appreciate intellectually, but which escapes my experience. He is brave, because he truly knows that what is his is untouchable by any power in the universe, his moral will and his judgments. And his sense of piety restricts his desire to those things only.

“Show me a man who is sick and happy, in danger and happy, dying and happy, in exile and happy, in disgrace and happy. Show him: I desire, by the gods, to see a Stoic.”

— Epictetus, Discourses II.19

The Stoic is equanimous in the face of those things which break down lesser folks. It is all to easy to fancy ourselves proficient when things are easy, yet here too we are deceived. In the face of loss, sickness, privation, and exile how sure are we in our philosophy?

“Will you not, as Plato says, study not to die only, but also to endure torture, and exile, and scourging, and, in a word, to give up all which is not your own?”

— Epictetus, Discourses IV.1

To lose all the things which others value: country, citizenship, estate, title, wealthy, health, life. To give back what is merely loaned, and to hold fast to that which is ours. Simple. Hard.

“Are you not the master of my body? What, then, is that to me? Are you not the master of my property? What, then, is that to me? Are you not the master of my exile or of my chains? Well, from all these things and all the poor body itself I depart at your bidding, when you please. Make trial of your power, and you will know how far it reaches.”

— Epictetus, Discourses IV.7

Epictetus was both a slave and an exile. His is experience is vastly different from my own, but if I can learn what he learned through his experience and ideas: that will be something.

“[A] philosopher should show himself cheerful and tranquil, so also he should in the things that relate to the body:

“See, ye men, that I have nothing, that I want nothing: see how I am without a house, and without a city, and an exile, if it happens to be so, and without a hearth I live more free from trouble and more happily than all of noble birth and than the rich. But look at my poor body also and observe that it is not injured by my hard way of living.” “

— Epictetus, Discourses IV.11

Epictetus often touts Diogenes of Sinope as his ideal Sage. He uses similar language to describe the Cynic, a philosopher appointed by God to call many away from the obfuscating fog of Typhos to the clarity of philosophy.

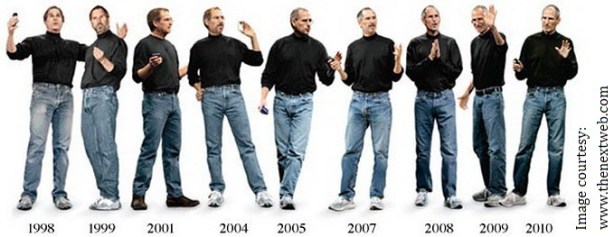

It’s hard to teach these things, hard to learn them this way. But to see the example makes it clear. Here is a person who does what he says, who lives what he teaches. Is he happy?

I’m in an exile of sorts theses days, here in Texas. Far from my friends and family, the land that I know and love. It’s hard for me to come to appreciate a new place, and in the back of my mind is simply the waiting to go back home.

Many of the judgement we make happen so quickly that they seem implicit. And undoing a faulty judgment is not easy task. While I know I can find happiness, virtue, and success here: it is in the back of my mind a temporary thing.

But that cuts both ways. It’s temporary, so I’m not overly concerned, but it’s not the temporary of a Stoic. A Stoic would like at all of life as temporary, and for that reason is not distressed. My perspective is not so broad. I’m still making progress.

This drives home another seemingly paradoxical Stoic position: that even through a Sage and non-sage might take the same action or view, the Sage’s action is perfect, katorthōma (κατόρθωμα), while the non-sage philosopher’s action is merely appropriate or in accordance with nature, kathēkon (καθῆκον).

This particular conundrum allowed me to really grok that for the first time, I think. My understanding of this particular issue isn’t any closer to resolution, but I think I’m starting to really get perfect versus appropriate actions.

The Stoics, as the Cynics before them, have the conception of the kosmopolitês (κοσμοπολίτης), the citizen-of-the-world. The Stoic conception is fairly different from they Cynic, so far as I understand, oikeiôsis (οἰκείωσις) having a feature in the Stoic version. This is another reason why we should not fear or be distressed in exile. We are rational creatures, fellow citizens in the cosmic-city of the Logos. How contrary to nature to scratch out a tiny plot of dirt, and choose to feel like a foreigner everywhere else?

The Stoics, as the Cynics before them, have the conception of the kosmopolitês (κοσμοπολίτης), the citizen-of-the-world. The Stoic conception is fairly different from they Cynic, so far as I understand, oikeiôsis (οἰκείωσις) having a feature in the Stoic version. This is another reason why we should not fear or be distressed in exile. We are rational creatures, fellow citizens in the cosmic-city of the Logos. How contrary to nature to scratch out a tiny plot of dirt, and choose to feel like a foreigner everywhere else?

It seems silly spelled out like that, but here I sit. In exile, a foreigner, here the word is gringo.

I guess I still have work to do.

Written in Exile,

— The MountainStoic

You must be logged in to post a comment.